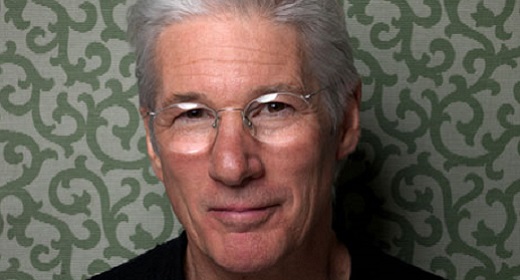

by Melvin McLeod: Richard Gere talks about his many years of Buddhist practice, his devotion to his teacher the Dalai Lama, and his work for Tibetan freedom….

![Awaken]()

I suppose it’s a sign of our current cynicism that we find it hard to believe celebrities can also be serious people. The recent prominence of “celebrity Buddhists” has brought some snide comments in the press, and even among Buddhists, but personally I am very appreciative of the actors, directors, musicians and other public figures who have brought greater awareness to the cause of Tibetan freedom and the value of Buddhist practice. These are fine artists and thoughtful people, some Buddhists, some not, among them Martin Scorsese, Leonard Cohen, Adam Yauch, Michael Stipe, Patti Smith, and of course, Richard Gere. I met Gere at his office in New York recently, and we talked about his many years of Buddhist practice, his devotion to his teacher the Dalai Lama, and his work on behalf of the dharma and the cause of the Tibetan people.

—Melvin McLeod

Melvin McLeod: What was your first encounter with Buddhism?

Richard Gere: I have two flashes. One, when I actually encountered the written dharma, and two, when I met a teacher. But before that, I was engaged in philosophical pursuit in school. So I came to it through Western philosophers, basically Bishop Berkeley.

Melvin McLeod: “If a tree falls in the forest and no one hears it, did it really happen?”

Richard Gere: Yes. Subjective idealism was his thesis—reality is a function of mind. It was basically the “mind only” school that he was preaching. Quite radical, especially for a priest. I was quite taken with him. The existentialists were also interesting to me. I remember carrying around a copy of Being and Nothingness, without knowing quite why I was doing it. Later I realized that “nothingness” was not the appropriate word. “Emptiness” was really what they were searching for—not a nihilistic view but a positive one.

My first encounter with Buddhist dharma would be in my early twenties. I think like most young men I was not particularly happy. I don’t know if I was suicidal, but I was pretty unhappy, and I had questions like, “Why anything?” Realizing I was probably pushing the edges of my own sanity, I was exploring late-night bookshops reading everything I could, in many different directions. Evans-Wentz’s books on Tibetan Buddhism had an enormous impact on me. I just devoured them.

Melvin McLeod: So many of us were inspired by those books. What did you find in them that appealed to you?

Richard Gere: They had all the romance of a good novel, so you could really bury yourself in them, but at the same time, they offered the possibility that you could live here and be free at the same time. I hadn’t even considered that as a possibility—I just wanted out—so the idea that you could be here and be out at the same time—emptiness—was revolutionary.

So the Buddhist path, particularly the Tibetan approach, was obviously drawing me, but the first tradition that I became involved in was Zen. My first teacher was Sasaki Roshi. I remember going out to L.A. for a three day sesshin [Zen meditation program]. I prepared myself by stretching my legs for months and months so I could get through it.

I had a kind of magical experience with Sasaki Roshi, a reality experience. I realized, this is work, this is work. It’s not about flying through the air; it’s not about any of the magic or the romance. It’s serious work on your mind. That was an important part of the path for me.

Sasaki Roshi was incredibly tough and very kind at the same time. I was a total neophyte and didn’t know anything. I was cocky and insecure and fucked up. But within that I was serious about wanting to learn. It got to the point at the end of the sesshin where I wouldn’t even go to the dokusan [interview with the Zen master]. I felt I was so ill-equipped to deal with the koans that they had to drag me in. Finally, it got to where I would just sit there, and I remember him smiling at that point. “Now we can start working,” he said. There was nothing to say—no bullshit, nothing.

Melvin McLeod: When someone has such a strong intuitive connection, Buddhism suggests that it’s because of karma, some past connection with the teachings.

Richard Gere: Well, I’ve asked teachers about that—you know, what led me to this? They’d just laugh at me, like I thought there was some decision to it or it was just chance. Well, karma doesn’t work that way. Obviously there’s some very clear and definite connection with the Tibetans or this would not have happened. My life would not have expressed itself this way.

I think I’ve always felt that practice was my real life. I remember when I was just starting to practice meditation—24 years old, trying to come to grips with my life. I was holed up in my shitty little apartment for months at a time, just doing tai chi and doing my best to do sitting practice. I had a very clear feeling that I’d always been in meditation, that I’d never left meditation. That it was a much more substantial reality than what we normally take to be reality. That was very clear to me even then, but it’s taken me this long in my life to bring it out into the world more, through more time practicing, watching my mind, trying to generate bodhicitta.

Melvin McLeod: When did you meet the Dalai Lama for the first time?

Richard Gere: I had been a Zen student for five or six years before I met His Holiness in India. We started out with a little small talk and then he said, “Oh, so you’re an actor?” He thought about that a second, and then he said, “So when you do this acting and you’re angry, are you really angry? When you’re acting sad, are you really sad? When you cry, are you really crying?” I gave him some kind of actor answer, like it was more effective if you really believed in the emotion that you were portraying. He looked very deeply into my eyes and just started laughing. Hysterically. He was laughing at the idea that I would believe emotions are real, that I would work very hard to believe in anger and hatred and sadness and pain and suffering.

That first meeting took place in Dharmsala in a room where I see him quite often now. I can’t say that the feeling has changed drastically. I am still incredibly nervous and project all kinds of things on him, which he’s used to at this point. He cuts through all that stuff very quickly, because his vows are so powerful, so all-encompassing, that he is very effective and skillful at getting to the point. Because the only reason anyone would want to see him is that they want to remove suffering from their consciousness.

It completely changed my life the first time I was in the presence of His Holiness. No question about it. It wasn’t like I felt, “Oh, I’m going to give away all my possessions and go to the monastery now,” but it quite naturally felt that this was what I was supposed to do—work with these teachers, work within this lineage, learn whatever I could, bring myself to it. In spite of varying degrees of seriousness and commitment since then, I haven’t really fallen out of that path.

Melvin McLeod: Does His Holiness work with you personally, cutting your neuroses in the many ways that Buddhist teachers do, or does he teach you more by the example of his being?

Richard Gere: There’s no question that His Holiness is my root guru, and he’s been quite tough with me at times. I’ve had to explain to people who sometimes have quite a romantic vision of His Holiness that at times he’s been cross with me, but it was very skillful. At the moment he did it, I’m not saying it was pleasant for me, but there was no ego attachment from his side. I’m very thankful that he trusts me enough to be the mirror for me and not pull any punches. Mind you, the first meetings were not that way; I think he was aware how fragile I was and was being very careful. Now I think he senses that my seriousness about the teachings has increased and my own strength within the teachings has increased. He can be much tougher on me.

Melvin McLeod: The Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism puts a strong emphasis on analysis. What drew you to the more intellectual approach?

Richard Gere: Yeah, it’s funny. I think what I probably would have been drawn to instinctively was Dzogchen [the Great Perfection teachings of the Nyingma school]. I think the instinct that drew me to Zen is the same one that would have taken me to Dzogchen.

Melvin McLeod: Space.

Richard Gere: The non-conceptual. Just go right to the non-conceptual space. Recently I’ve had some Dzogchen teachers who’ve been kind enough to help me, and I see how Dzogchen empowers much of the other forms of meditation that I practice. Many times Dzogchen has really zapped me into a fresh vision and allowed me to see a kind of limited track that I was falling into through conditioning and basic laziness.

But overall, I think the wiser choice for me is to work with the Gelugpas, although space is space wherever it is. I think the analytical approach—kind of finding the non-boundaries of that space—is important. In a way, one gets stability from being able to order the rational mind. When space is not there for you, the intellectual work will still keep you buoyed up. I still find myself in situations where my emotions are out of control and the anger comes up, and it’s very difficult to enter pure white space at that point. So the analytical approach to working with the mind is enormously helpful. It’s something very clear to fall back on and very stabilizing.

Melvin McLeod: What was the progression of practices for you, to the extent that you can talk about it, after you entered the vajrayana path?

Richard Gere: I’m a little hesitant to talk about this because, one, I don’t claim to know much, and two, being a celebrity these things get quoted out of context and sometimes it’s not beneficial. I can say that whatever forms of meditation I’ve taken on, they still involve the basic forms of refuge, generation of bodhicitta [awakened mind and heart] and dedication of merit to others. Whatever level of the teachings that my teachers allow me to hear, they still involve these basic forms.

Overall, tantra has become less romantic to me. It seems more familiar. That’s an interesting stage in the process, when that particular version of reality becomes more normal. I’m not saying it’s normal, in the sense of ordinary or mundane, but I can sense it being as normal as what I took to be reality before. I can trust that.

Melvin McLeod: What dharma books have meant a lot to you?

Richard Gere: People are always asking me what Buddhist books I would recommend. I always suggest Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind to someone who says, “How can I start?” I’ll always include something by His Holiness. His book Kindness, Clarity and Compassion is extraordinarily good. There’s wonderful stuff in there. Jeffrey Hopkins’ The Tantric Distinction is very helpful. There are so many.

Melvin McLeod: You go to India often. Does that give you the opportunity to practice in a less distracted environment?

Richard Gere: Actually it’s probably more distracting! When I go there, I’m just a simple student like everyone else, but I’m also this guy who can help. When I’m in India there are a lot of people who require help and it’s very difficult to say no. So it’s not the quietest time in my life, but just being in an environment where everyone is focusing on the dharma and where His Holiness is the center of that focus is extraordinary.

Melvin McLeod: When you’re in Dharmsala do you have the opportunity to study with the Dalai Lama or other teachers there?

Richard Gere: I’ll try to catch up with all my teachers. Some of them are hermits up in the hills, but they come down when His Holiness gives teachings. It’s a time to catch up on all of it, and just remember. For me, it means remembering. Life here is an incredible distraction and it’s very easy to get off track. Going there is an opportunity to remember, literally, what the mission is, why we’re here.

Melvin McLeod: Here you’re involved in a world of film-making that people think of as extremely consuming, high-powered, even cut-throat.

Richard Gere: That’s all true. But it’s like everyone else’s life, too. It just gets into the papers, that’s all. It’s the same emotions. The same suffering. The same issues. No difference.

Melvin McLeod: Do you find that you have a slightly split quality to your life, going back and forth between these worlds?

Richard Gere: I find that more and more my involvement in a career, in a normal householder life, is a great challenge for deepening the teachings inside of me. If I weren’t out in the marketplace, there’s no way I would be able to really face the nooks and crannies and darkness inside of me. I just wouldn’t see it. I’m not that tough; I’m not that smart. I need life telling me who I am, showing me my mind constantly. I wouldn’t see it in a cave. The problem with me is I would probably just find some blissful state, if I could, and stay there. That would be death. I don’t want that. As I said, I’m not an extraordinary practitioner. I know pretty much who I am. It’s good for me to be in the world.

Melvin McLeod: Are there any specific ways you try to bring dharma into your work, beyond working with your mind and trying to be a decent human being?

Richard Gere: Well, that’s a lot! That’s serious shit.

Melvin McLeod: That’s true. But those are the challenges we all face. I was just wondering if you try to bring a Buddhist perspective to the specific world of film?

Richard Gere: In film, we’re playing with something that literally fragments reality, and being aware of the fragmentation of time and space I think lends itself to the practice, to loosening the mind. There is nothing real about film. Nothing. Even the light particles that project the film can’t be proven to exist. Nothing is there. We know that when we’re making it; we’re the magicians doing the trick. But even we get caught up in thinking that it is all real—that these emotions are real, that this object really exists, that the camera is picking up some reality.

On the other hand, there is some magical sense that the camera sees more than our eyes do. It sees into people in a way that we don’t normally. So there’s a vulnerability to being in front of the camera that one doesn’t have to endure in normal life. There’s a certain amount of pressure and stress in that. You are being seen, you are really being seen, and there is no place to hide.

Melvin McLeod: But there’s no way you actually work with the product to…?

Richard Gere: You mean teaching through that? Well, I think these things are far too mysterious to ever do that consciously, no. Undoubtedly, as ill-equipped to be a good student as I am, I’ve had a lot of teachings, and some have stuck. Somehow they do communicate-not because of me, but despite me. So I think there is value there. It’s the same as everyone: whatever positive energies have touched them in myriad lifetimes are going to come through somehow. When you look into their eyes, when the camera comes in for a closeup, there’s something there that is mysterious. There’s no way you can write it, there’s no way you can plan it, but a camera will pick it up in a different way than someone does sitting across the table.

Melvin McLeod: How comfortable are you with your role as the spokesman for the dharma?

Richard Gere: For the dharma? I’ve never, ever accepted that, and I never will. I’m not a spokesman for dharma. I lack the necessary qualities.

Melvin McLeod: But you are always being asked in public about being a Buddhist.

Richard Gere: I can talk about that only as a practitioner, from the limited point of view that I have. Although it’s been many years since I started, I can’t say that I know any more now than I did then. I can’t say I have control over my emotions; I don’t know my mind. I’m lost like everyone else. So I’m certainly not a leader. In the actual course of things, I talk about these things, but only in the sense that this is what my teachers have given me. Nothing from me.

Melvin McLeod: When you are asked about Buddhism, are there certain themes you return to that you feel are helpful, such as compassion?

Richard Gere: Absolutely. I will probably discuss wisdom and compassion in some form, that there are two poles we are here to explore—expanding our minds and expanding our hearts. At some point hopefully being able to encompass the entire universe inside mind, and the same thing with heart, with compassion, hopefully both at the same time. Inseparable.

Melvin McLeod: When you say that, I’m reminded of something that struck me when I saw the Dalai Lama speak. He was teaching about compassion, as he so often does, but I couldn’t help but wonder what would happen if he spoke more to a wider audience about the Buddhist understanding of wisdom, that is, emptiness. I just wondered what would happen if this revered spiritual leader said to the world, well, you know, all of this doesn’t really exist in any substantive way.

Richard Gere: Well, the Buddha had many turnings of the wheel of dharma, and I think His Holiness functions in the same way. If we are so lost in our animal natures, the best way to start to get out of that is to learn to be kind. Someone asked His Holiness, how can you teach a child to care about and respect living things? He said, see if you can get them to love and respect an insect, something we instinctively are repulsed by. If they can see its basic sentience, its potential, the fullness of what it is, with basic kindness, then that’s a huge step.

Melvin McLeod: I was just reading where the Dalai Lama said that he thinks mother’s love is the best symbol for love and compassion, because it is totally disinterested.

Richard Gere: Nectar. Nectar is that! [In vajrayana practice, spiritual blessings are visualized as nectar descending on the meditator.] That’s mother’s milk; that’s coming right from mom. Absolutely.

Melvin McLeod: Although you are cautious in speaking about the dharma, you are a passionate spokesman on the issue of freedom for Tibet.

Richard Gere: I’ve gone through a lot of different phases with that. The anger that I might have felt twenty years ago is quite different now. We’re all in the same boat here, all of us—Hitler, the Chinese, you, me, what we did in Central America. No one is devoid of the ignorance that causes all these problems. If anything, the Chinese are just creating the cause of horrendous future lifetimes for themselves, and one cannot fail to be compassionate towards them for that.

When I talk to Tibetans who were in solitary confinement for twenty or twenty-five years, they say to me, totally from their heart, that the issue is larger than what they suffered at the hands of their torturer, and that they feel pity and compassion for this person who was acting out animal nature. To be in the presence of that kind of wisdom of heart and mind—you can never go back after that.

Melvin McLeod: It is remarkable that an entire people, generally, is imbued with a spirit like that.

Richard Gere: I’m convinced that it is because it was state-oriented. Obviously, problems come with that, with no separation of church and state. But I am convinced that the great dharma kings manifested to actually create a society based on these ideas. Their institutions were designed to create good-hearted people; everything in the society was there to feed it. That became decadent—there were bad periods, there were good periods, whatever. But the gist of the society was to create good-hearted people, bodhisattvas, to create a very strong environment where people could achieve enlightenment. Imagine that in America! I mean, we have no structure for enlightenment. We have a very strong Christian heritage and Jewish heritage, one of compassion, one of altruism. Good people. But we have very little that encourages enlightenment—total liberation.

Melvin McLeod: Looking at how human rights violations have come to the forefront of world consciousness, such as in Tibet and South Africa before that, the work of celebrities such as yourself who have been able to use their fame skillfully has been an important factor.

Richard Gere: I hope that’s true. It’s kind of you to say. It’s an odd situation. Previously I’d worked on Central America and some other political and human rights issues, and got to know the ropes a bit in working with Congress and the State Department. But that didn’t really apply to this situation. Tibet was too far away, and there had been extremely limited American involvement there.

I found also that the question of His Holiness in terms of a political movement was very tricky. It’s a non-violent movement, which is a problem in itself—you don’t get headlines with nonviolence. And His Holiness doesn’t see himself as Gandhi; he doesn’t create dramatic, operatic situations.

So we’ve ended up taking a much steadier kind of approach. It’s not about drama. It’s about, little by little, building truth, and I think it’s probably been deeper because of that. The senators, congressmen, legislators and parliamentarians who have got involved go way beyond what they would normally give to a cause they believed in.

I think the universality of His Holiness’ words and teachings have made this so much bigger than just Tibet. When His Holiness won the Nobel Peace Prize, there was a quantum leap. He is not seen as solely a Tibetan anymore; he belongs to the world. We were talking before about what the camera picks up—just a picture of His Holiness seems to communicate so much. Just to see his face. It’s arresting, and at the same time it’s opening. You can imagine what it would have been like to see the Buddha. Just to see his face would put you so many steps ahead. I think a lot of what we have done is just putting His Holiness in situations where he could touch as many people as possible, which he does every time with impeccable bodhicitta.

I keep saying Tibet will be taken care of in the process, but it’s about saving every sentient being, and as long as we keep our eyes on that prize, Tibet will be all right. Of course there are immediate issues to deal with in Tibet. We work on those all the time. Although we had reason to believe a more open communication with the Chinese was evolving, the optimism generated by Clinton’s visit to China has not panned out. In fact, the Tibetans, as well as the pro-democracy Chinese, are experiencing the most repressive period since the late eighties, since Tienanmen Square.

Melvin McLeod: I’m always impressed with a point the Dalai Lama makes which is very similar to what my own teacher, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, presented in the Shambhala teachings. That is the need for a universal spirituality based on simple truths of human nature that transcends any particular religion, or the need for formalized religion at all. This strikes me as an extraordinarily important message.

Richard Gere: Well, I think it’s true. His Holiness says that what we all have in common is an appreciation of kindness and compassion; all the religions have this. Love. We all lean towards love.

Melvin McLeod: But even beyond that, he points out that billions of people don’t practice a religion at all.

Richard Gere: But they have the religion of kindness. They do. Everyone responds to kindness.

Melvin McLeod: It’s fascinating that a major religious leader espouses in effect a religion of no religion.

Richard Gere: Sure, that’s what makes him larger than Tibet.

Melvin McLeod: It makes him larger than Buddhism.

Richard Gere: Much larger. The Buddha was larger than Buddhism.

Melvin McLeod: You are able to sponsor a number of projects in support of the dharma and of Tibetan independence.

Richard Gere: I’m in kind of a unique position in that I do have some cash in my foundation, so I’m able to offer some front money to various groups to help them get projects started. Sponsoring dharma books is important to me—translation, publishing—but I think the most important thing I can do is help sponsor teachings. To work with His Holiness and help sponsor teachings in Mongolia, India, the United States and elsewhere-nothing gives me more joy.

The program we’re doing this summer is four days of teachings by the Dalai Lama in New York. August 12 to 14 will be the formal teaching by His Holiness on Kamalashila’s “Middle-length Stages of Meditation” and “The Thirty-seven Practices of the Bodhisattvas.” That’s at the Beacon Theater and there are about 3,000 tickets available. I’m sure those will sell quickly. If people can’t get into that, there’s going to be a free public teaching in Central Park on the fifteenth. We’re guessing there will be space for twenty-five to forty thousand people, so whoever wants to come will be able to. His Holiness will give a teaching on the Eight Verses of Mind Training, a very powerful lojong teaching, one of my favorites actually. Then His Holiness will give a wang, a long life empowerment of White Tara.

I’ve seen His Holiness give bodhicitta teachings like these, and no one can walk away without crying. He touches so deep into the heart. He gave a teaching in Bodh Gaya last year on Khunu Lama’s “In Praise of Bodhicitta,” which is a long poems Just thinking about it now, I’m starting to crys So beautiful. When he was teaching on Kunu Lama’s “In Praise of Bodhicitta,” who was his own teachers whooosh! We were inside his heart, in the most extraordinary way. A place you can’t be told about, you can’t read about, nothing. You’re in the presence of Buddha. I’ve had a lot of teachers who give wonderful teachings on wisdom, but to see someone who really, really has the big bodhicitta, real expanded bodhicittas.

So those are the teachings that I believe His Holiness is here to give. That’s what touches.

Greatly realized beings who attain the rainbow body at the time of death leave behind only nails, hair, and occasionally cartilage. They dissolve into the middling level of the trinity; the light/sound/bliss level; represented by the holy spirit in Christianity. The dissolution process may take up to seven days, during which time the body shrinks progressively. There are incidents of “partial rainbow body attainments” in which the master or yogi halts the dissolution process before it is complete in order to leave behind

Greatly realized beings who attain the rainbow body at the time of death leave behind only nails, hair, and occasionally cartilage. They dissolve into the middling level of the trinity; the light/sound/bliss level; represented by the holy spirit in Christianity. The dissolution process may take up to seven days, during which time the body shrinks progressively. There are incidents of “partial rainbow body attainments” in which the master or yogi halts the dissolution process before it is complete in order to leave behind